Copyright © 2018 Polish Airmen’s Association UK | 238 - 246, King Street, London W6 0RF | email: zlplondyn@btinternet.com

This selection of photographs are from the collection of Lesław Latawiec 704538 © Lesław Latawiec 2015 All rights reserved

The Poles were impatient to see action, but the Royal Air Force would not at first let them fly operationally because few of the newcomers spoke English and there was understandable concern about their morale. What the RAF did not yet realise was that the Poles were excellent pilots. Having come through the 1939 Campaign and the Battle of France, they had undergone a process of “natural selection.” The Polish pilots also had more combat experience than most of their British counterparts, and they employed formations and tactics more flexible - and more deadly - than those of the RAF. The exiles were, above all, motivated by a deep patriotism and a burning desire to defeat the enemy and return to those they loved. As the Battle of Britain wore on, the shortage of trained pilots forced Fighter Command to introduce Polish airmen into British squadrons. Two national units, 302 (“Poznański") Squadron and 303 (“Kościuszki") Squadron were also formed and equipped with Hurricanes. The Polish pilots now set about defending Britain's airspace with courage, skill and a will to win.

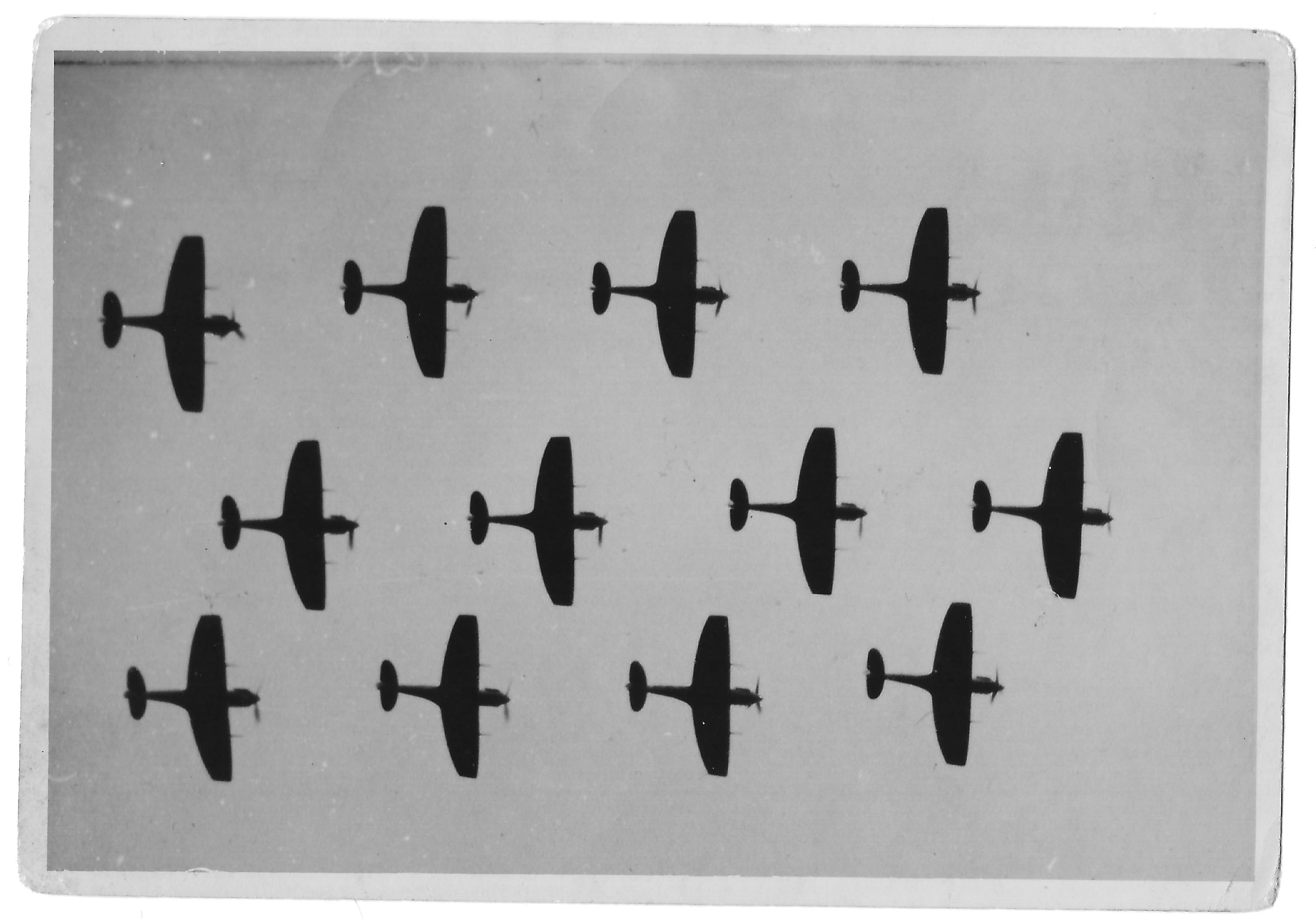

The Polish airmen reinforced Fighter Command in the weeks from the middle of August to the middle of September when it appeared that the RAF might well lose the Battle. The statistics make interesting reading. The 146 Polish pilots, some 5% of Fighter Command's strength, claimed 203 German aircraft destroyed for the loss of 29 killed. This represents 15% of the RAF's total number of victories or 1.4 enemy aircraft for every Pole engaged. At the same time the two national squadrons suffered losses 70% lower than most RAF units. On the 15 September, celebrated in the United Kingdom as 'Battle of Britain Day', one in five of the pilots in action was Polish. At the end of the 16-week campaign, the top-scoring Fighter Command unit was 303 Squadron, which in only 42 days was credited with 126 enemy machines. And arguably the most successful individual pilot - with 17 victories - was Sergeant Josef Frantiśek, a Czech who also flew with '303.'

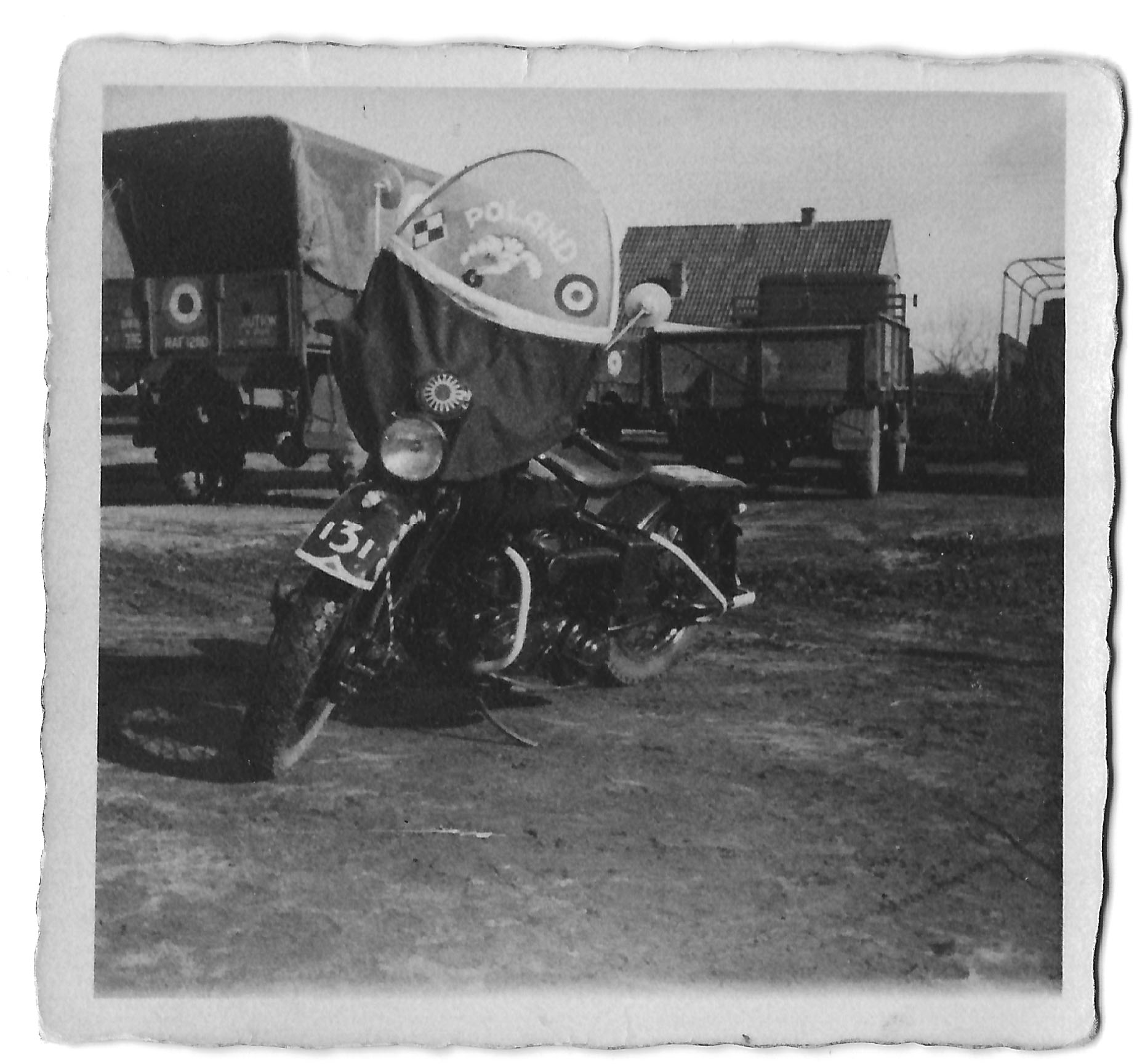

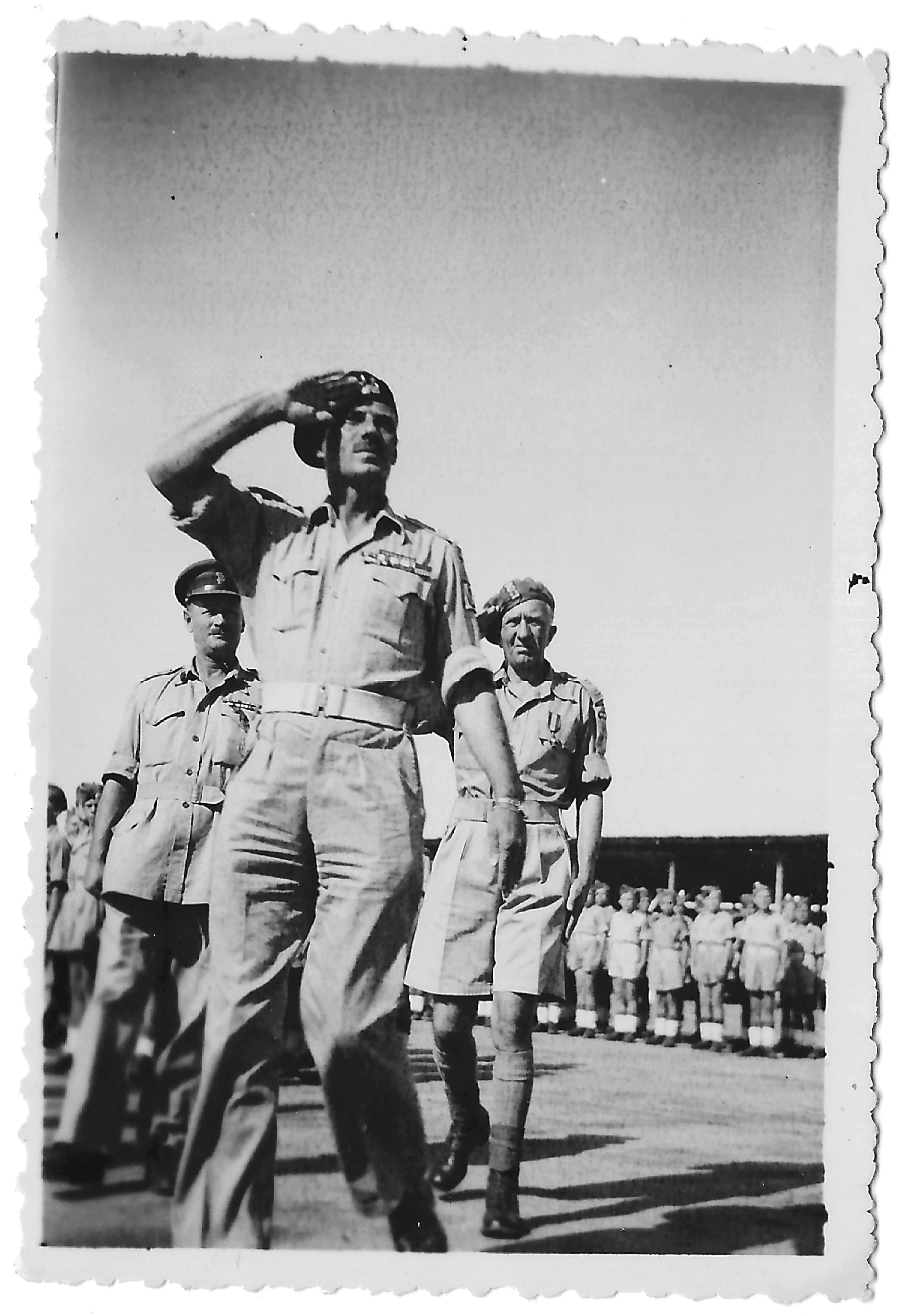

When they heard how well the Poles were fighting, the British people took them to their hearts. The King visited 303 Squadron at their base at Northolt and signed their unofficial diary; in Cabinet it was said that 'the morale of the Polish pilots is excellent and their bravery much above the average'; and young British women competed for the honour of dating a dashing Polish “Fighter Boy.” Indeed, such was the appeal of the exiles to the opposite sex, British airmen took to wearing “Poland” flashes and speaking in broken English in the hope of improving their chances.

The Poles had more than proved themselves, and a grateful RAF now rose to the challenge of integrating them into its structure. By an agreement of August 1940, the Polish Air Force attained independent status, although the RAF retained operational control. The Polish Air Force grew, and by the end of the war, there were 14,000 airmen and airwomen serving with 15 front-line squadrons of the highest quality as well as with numerous technical and training units. Polish personnel served in all commands, and in all theatres, and earned a reputation for exceptional courage and devotion to duty. Poles also continued to serve with the RAF and PAF officers commanded British units. To its credit, the RAF respected the culture and traditions of its allies and it recognised their equality with British nationals. The Poles in turn appreciated the RAF, which, according to veterans, was efficient, fair and understanding of their needs.

Nine of the Polish squadrons were conceived as fighter units. After the Battle of Britain, Fighter Command went on the offensive and Polish pilots participated in every major air battle fought by the home-based RAF. Whether flying 'sweeps' over France, attacking enemy installations or escorting bomber formations deep into occupied Europe, the Polish fighter squadrons flew and fought superbly. Their superiority was demonstrated in April 1942 when 11 Group staged a gunnery competition. The top-scoring RAF squadron finished fourth with 130 points, but the top three places were taken by 315 Squadron, with 183 points, '302', with 432 points and '303' with a staggering 808 points. By the end of the war, Polish fighter pilots serving with the Polish, British and American air forces had accounted for 957 enemy aircraft, had probably destroyed 196 and had damaged a further 280. No fewer than 58 of these pilots became 'aces', destroying five or more enemy aircraft. The top scoring Polish fighter aces were Group Captain Witold Urbanowicz and Wing Commander Stanislaw Skalski, both of whom had 18 confirmed kills.

The Poles thought about the business of air fighting and they were never afraid to innovate. Polish pilots were especially popular with American bomber crews because they stayed with their charges when flying escort missions and they developed special tactics to protect them from the defending German fighters. Flight Lieutenant Janusz Lewkowicz, a pilot on 309 Squadron, meanwhile calculated that with careful fuel conservation his Mustang fighter had sufficient range to reach Norway from his base in Scotland. On 27 June 1942 Lewkowicz made an unauthorised, but highly successful, flight to Norway, which earned him an official reprimand and unofficial congratulations. Soon Allied fighters were regularly attacking targets in Norway.

Three Polish Fighter Wings were eventually created, but from 1941 to 1943 most of the PAF's victories were credited to the 1st Polish Fighter Wing based at RAF Northolt. Northolt was and remains the PAF's spiritual home in Britain; and it is the last Battle of Britain station in the London area still used by the RAF. The character of Northolt was shaped profoundly by the exiles and it became so thoroughly Polonized a sign hung in the bar of the Officer's Mess saying “English Spoken Here.”

Four Polish bomber squadrons were formed, Nos. '300', '301', '304' and '305', but the PAF with its limited reserves of manpower fought a losing battle to keep them up to strength. In July 1940, 300 Squadron became the first Polish flying unit to be formed; and by the end of the war it had carried out more operations, and suffered heavier losses, than any other allied squadron. '301' served with Bomber Command until severe losses forced its disbandment in April 1943. Some of its crews went on to serve with 1586 (Special Duties) Flight, flying arms and supplies to the Polish Home Army and other resistance groups in occupied Europe from bases in Italy. They are perhaps best remembered for their part in the airlift mounted by Polish, British, South African and American airmen in an attempt to keep the people of Warsaw supplied during the gallant, but ill-fated, Uprising of August to October 1944. Similarly, 304 Squadron suffered heavy losses and it was decided to transfer the unit to Coastal Command. It remained there for the rest of the war, working tirelessly to help keep Britain's vital sea lanes open. 305 Squadron flew with Bomber Command until September 1943, when it transferred to 2nd Tactical Air Force. The Squadron flew successful day and night operations against targets in Normandy and across North-West Europe until VE-Day. Polish squadrons in Bomber Command and Coastal Command dropped a total of 14,708 tons of bombs and mines on enemy targets.

At the same time, in Italy, 318 Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron and 663 Artillery Observation Squadron did valuable work in support of the 2nd Polish Corps of the 8th Army. None of this would have been possible without the support of the Polish Air Force's ground crews whose dedication, resourcefulness and capacity for hard work made for high rates on serviceability on the national squadrons.

In December 1943 Pomocnicza Lotnicza Służba Kobiet (PLSK), a Polish section of Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was announced. A total of 1,426 women served with the PLSK, and many of these were former inmates of Soviet and German concentration camps. Fourteen Polish men volunteered to serve as ferry pilots with the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). They were joined by three Polish women, Stefania Wojtulanis, Anna Leska and Jadwiga Piłsudska, the daughter of Marshal Józef Pilsudski.

In March 1943, the 15 hand-picked pilots of the Polish Fighting Team arrived in Tunisia. This unit was led by Skalski, and it included men of the calibre of Ludwik Martel and Eugeniusz Horbaczewski. Flying Spitfires, 'Skalski's Circus' in less than two months shot down 25 enemy aircraft, probably destroyed three and damaged nine more for the loss of one pilot taken prisoner. However, the victories were largely incidental for the PFT had come to North Africa not to fight but to learn the techniques of highly mobile warfare developed by the Desert Air Force. These they would apply during the forthcoming invasion of the European continent on 6 June 1944 and in the subsequent campaigns in Normandy and North-West Europe.

Shortly after the invasion, the first V-1 flying bombs fell on Britain. These entirely indiscriminate weapons had been discovered by the Polish Home Army in 1943 and, acting on their information, the RAF had bombed the research centre at Peenemünde. This delayed production of the V-1 for six months. It also slowed the development of the more frightening V-2 long-range rocket against which there could be no defence. With characteristic courage and ingenuity, the Home Army eventually obtained an intact V-2, which was dismantled and the parts flown back to RAF Hendon on 28 July 1944. At the receiving end in Britain, the Polish pilots of 133 Wing joined the battle against the V-1s which they nicknamed 'Witches'. They did an excellent job, destroying a total of 190 'Witches' before they fell on London.

The Yalta Agreement signed by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin in February 1945 ensured that Poland would become a satellite of the Soviet Union. Though everything the Poles had fought for was now lost, to their great credit they continued to fight out of duty to their homeland and loyalty to their British and allied brothers in arms. The war went on and the Polish Air Force continued to fly and fight as the Third Reich slowly ground to a halt. On 25 April 1945, the Lancasters of 300 Squadron, escorted by 303 Squadron's Mustangs, attacked Hitler's mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden. This would be the last operational mission of the war for both Squadrons.

Tragically, whereas the exiles from Western Europe returned to their homelands as liberators, the Poles watched helplessly as their country was taken over by the communists. As those that returned home risked death or imprisonment, most opted to remain in the UK or to begin new lives abroad. For political reasons, Polish servicemen and servicewomen were excluded from the Victory Parade in London in June 1946. The Poles, who had fought so hard and sacrificed so much, felt they had been betrayed. Nevertheless, veterans remembered their years as brothers-in-arms of the RAF with pride and affection. The British airmen admired the men and women who had fought alongside them and hundreds of Poles were re-admitted to the peacetime air force.

In all, 2,408 Polish airmen gave their lives during the war and a memorial was raised in their honour at Northolt from funds contributed by Polish and RAF veterans and the British public. Unveiled on the 2nd of November 1948, the memorial bears an apt inscription:

"Stoczyłem piękną walkę, bieg ukończyłem, wiary nie straciłem."

"I have fought the good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith."

In 1990, 51 years after the German and Soviet invasions, Poland at last took its place among the free nations of the world. In September 2003, the British Government at last apologised for refusing to permit Polish participation in the Victory Parade 57 years before.

Poland was left under the rule of the USSR and the Polish Government in Exile established during the war years remained in Great Britain.The Polish Air Force Association was formed in June 1945 to look after the interests of its personnel in exile.

Brief History of the Polish Air Force

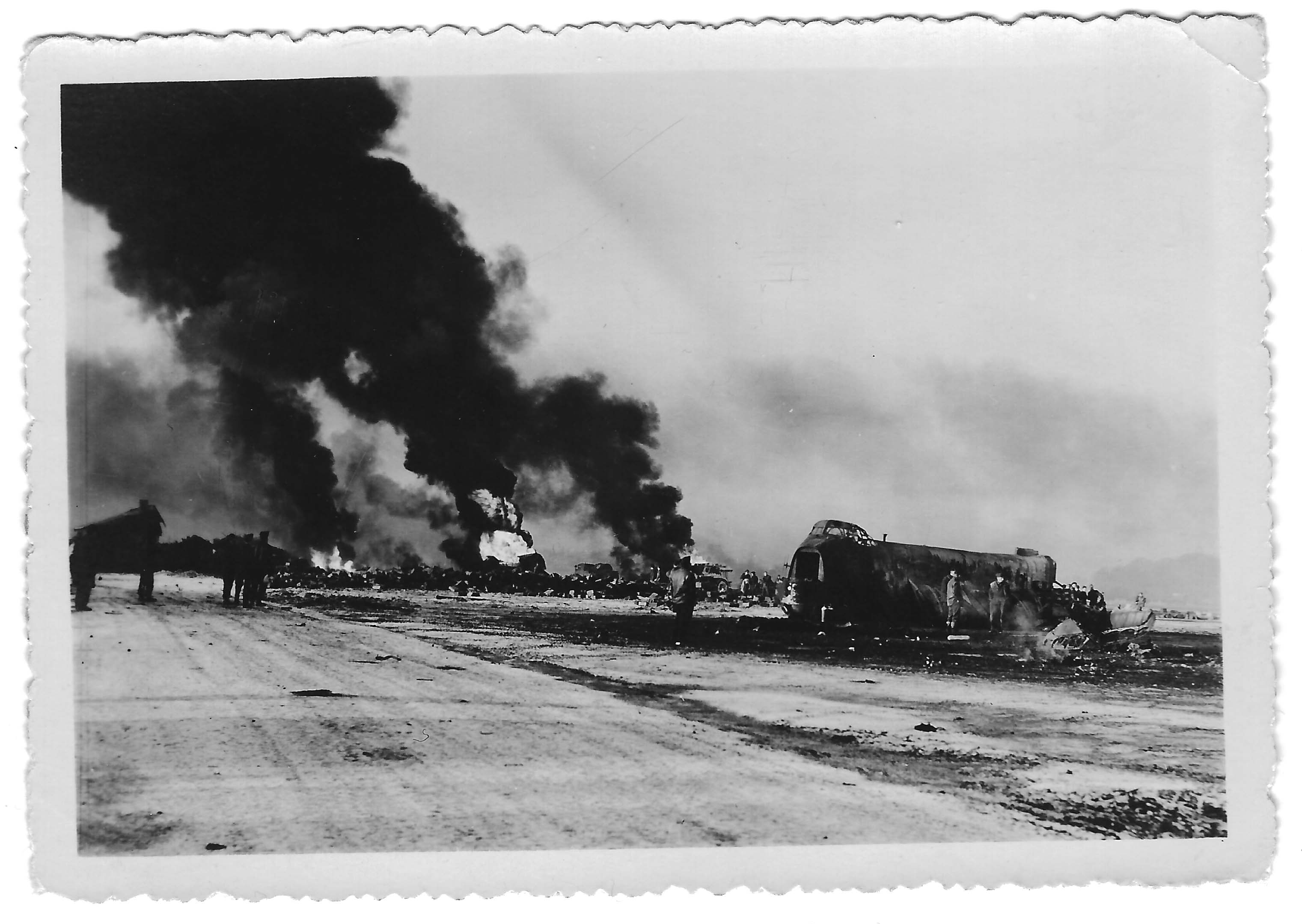

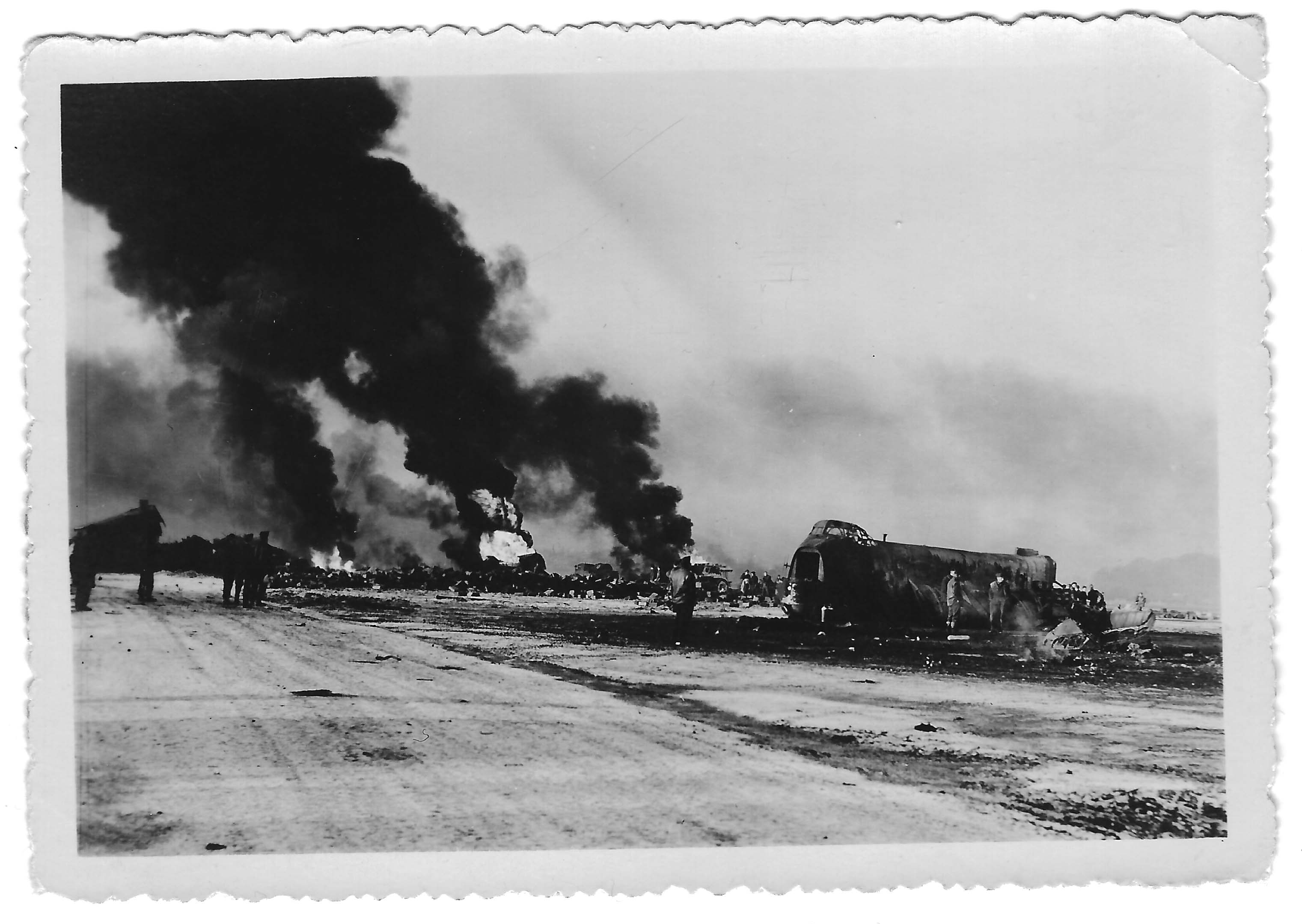

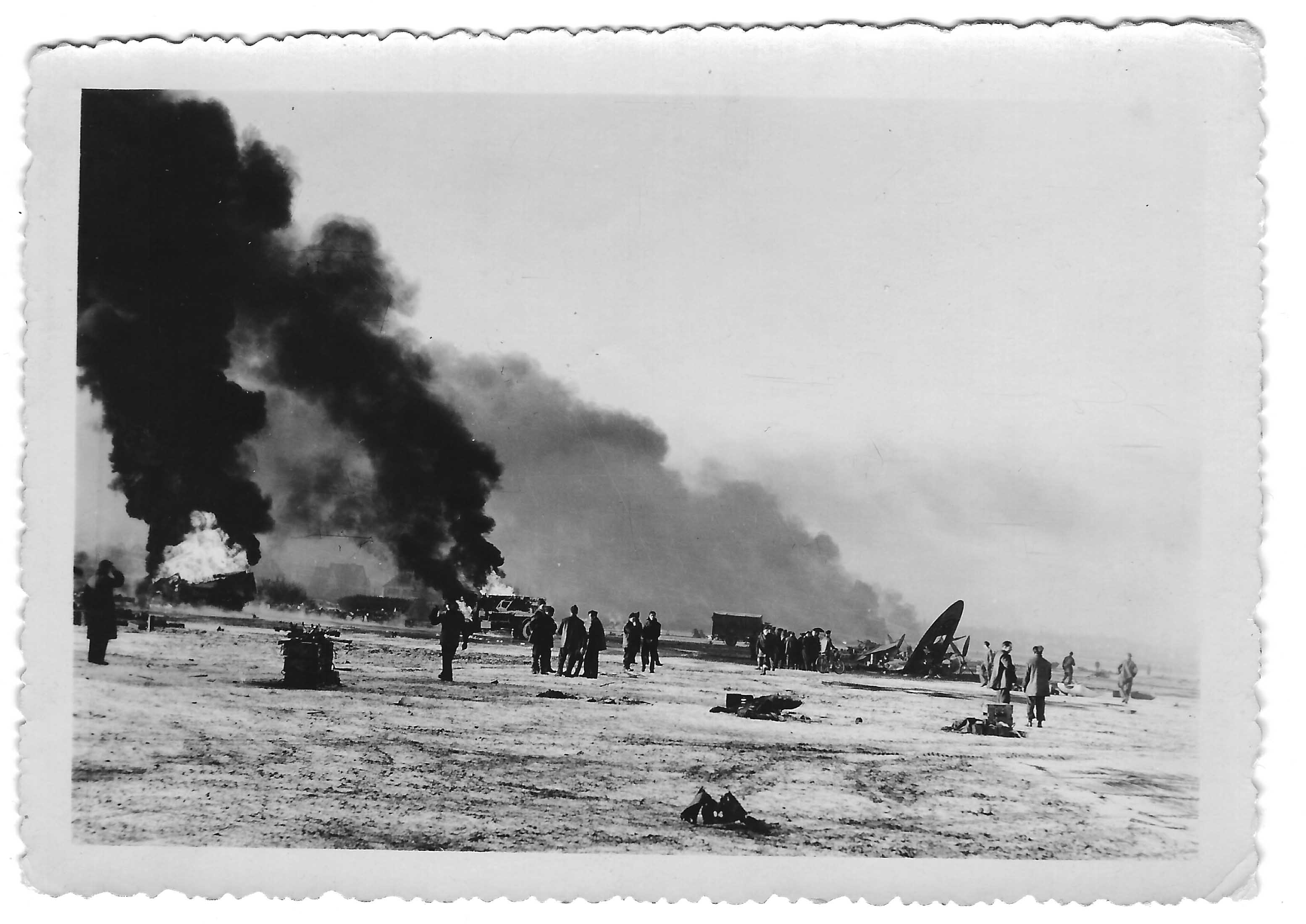

With the outbreak of war, on 1st September 1939, the Polish Air Force's mostly obsolete aircraft were opposed by the German Luftwaffe equipped with over 1,300 modern fighters and bombers. The PAF's Eskadry were not, however, destroyed on the ground in the first days of the campaign, as is often asserted, but had been intelligently dispersed to forward airfields. Furthermore, although flying outdated aircraft, the Polish pilots fought well; and in the brief campaign shot down 126 enemy machines for the loss of 114 of their number. Following the Soviet invasion and German victory, most of the Polish airmen were interned in camps in Romania and elsewhere before escaping to France to continue the war. Once there, the exiles' superior training and that most precious commodity - combat experience - stood them in good stead. Though only engaged in the latter stages of the campaign, 130 Polish pilots serving in the French Air Force destroyed 60 German aircraft and suffered 13 killed. After the Fall of France, in June 1940, some 8,500 Polish airmen escaped across the English Channel. Having been driven from their homeland in 1939, only to be forced to flee again, the Poles now called Britain, Wyspa Ostatniej Nadziei or 'The Island of Last Hope.'